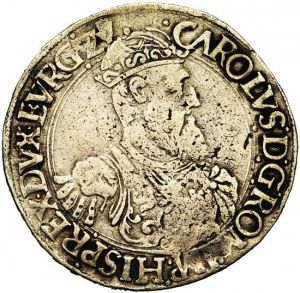

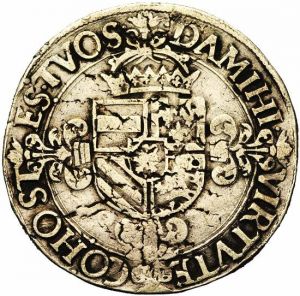

Brabant (1544-48) silver florin

This specimen was lot 514 in Jean Elsen sale 124 (Brussels, March 2015), where it sold for €1,200 (about US$1,496 including buyer's fees). The catalog description[1] noted,

"BRABANT, Duché, Charles Quint (1506-1555), AR florin Karolus d'argent, s.d. (1544-1548), Anvers. Premier type. Droit: B. couronné et cuirassé de l'empereur à droite, la barbe longue. Revers: Ecu d'Autriche-Bourgogne posé sur une croix fleuronnée coupant la légende. (duchy of Brabant, Charle V (1506-55), silver Karolus florin, undated, Antwerp mint, first type. Obverse: crowned and armored bust of the emperor to right with long beard. Reverse: arms of Austria-Burgundy over a floriate cross, dividing the legend. Fine to very fine.)

La découverte de nouvelles mines d'argent au Tyrol et en Saxe permit aux seigneurs et aux souverains qui les possédaient de frapper, à partir de la fin du 15e siècle, de grosses monnaies d'argent de la valeur d'un florin d'or, appelées pour cette raison Guldengroschen. Le comte de Schlick en Bohême commença en 1519 l'exploitation d'une riche mine d'argent à Joachimstal. Bientôt les Joachimstaler Guldengroschen innondèrent l'Empire et les Pays-Bas où ils prirent le nom taler, daalder et daldre. Ces grosses monnaies d'argent furent longtemps interdites dans les Pays-Bas où l'on préférait la monnaie d'or pour effectuer les paiements plus importants. De plus, l'arrivage de l'argent du Nouveau Monde via l'Espagne, ne devint important qu'après la découverte des mines de Potosi (Bolivie) en 1545 et de Zacateca (Mexique) en 1546. L'innovation monétaire majeure du règne de Charles Quint fut l'introduction de la première grosse monnaie d'argent dans les Pays-Bas qui fut ordonnée en avril 1544. Comparable aux talers allemands et impériaux, sa valeur fut fixée égale à celle du florin Karolus d'or introduit en 1521 au cours de 20 sous ou 20 patards (stuivers). Le florin Karolus d'argent ne connut pas le succès escompté auprès du public et sa frappe fut abandonnée après la deuxième émission. Beau à Très Beau. (The dsicovery of new silver mines in Tyrol and Saxony permitted the lords and sovereigns who possesed them to strike, after the end of the fifteenth century, large silver coins of the value of a gold florin and called goldgulden. The count of Schlick commenced in 1519 the exploitation of a rich silver mine at Joachimsthal. From thence the Joachimstaler Guldengroschen inundated the Empire and the Low Countries where they took the name thaler, daalder or daldre. These large coins were long banned from the Low Countries where gold was preferred for important payments. Then, the arrival of silver from the New World via Spain became important after the discovery of the mines of Potosi in 1545 and Zacatecas in Mexico in 1546. The major monetary innovation of the reign of Charles V was the introduction of the first large silver coin by the ordinance of April 1544. Comparable to Imperial and German thalers, their value was fixed equal to that of the karolus d'or introduced in 1521 at the value of 20 sous or 20 stuivers. This coin was not successful and was abandoned after the second issue.)"

This rare type is not mentioned in Davenport, either because he was not aware of it or because it is too light to be counted as a thaler.

Reported Mintage: unknown.

Specification: silver, this specimen 22,13 g.

Catalog reference: G.H., 187-1; Delm-1; W., 667.

- Davenport, John S., European Crowns, 1484-1600, Frankfurt: Numismatischer Verlag, 1977.

- [1]Elsen, Philippe, et al., Vente Publique 124, Brussels: Jean Elsen et ses Fils S.A., 2015.

Link to: